Introducing wine tech from the space-age

Jo Gilbert takes a deep dive into Deep Planet – the revolutionary diagnostics tool that works with the European Space Agency to offer vineyard management advice.

Deep Planet’s VineSignal system is perhaps one of the more exciting innovations to have landed in vineyards in recent years.

Founded by three Oxford University graduates just months after completing an MBA in 2018, the system uses an intricate mix of satellite imagery and sophisticated AI tools – as well as wineries’ own data – in order to answer winemakers’ most pressing questions.

Incredibly, the satellites can capture detailed imagery of any vines, anywhere in the world, with up to five years of data already in the bank. Every three to five days, new data is collected via satellites passing through the stratosphere, which VineSignal can then feed into its machine-learning models.

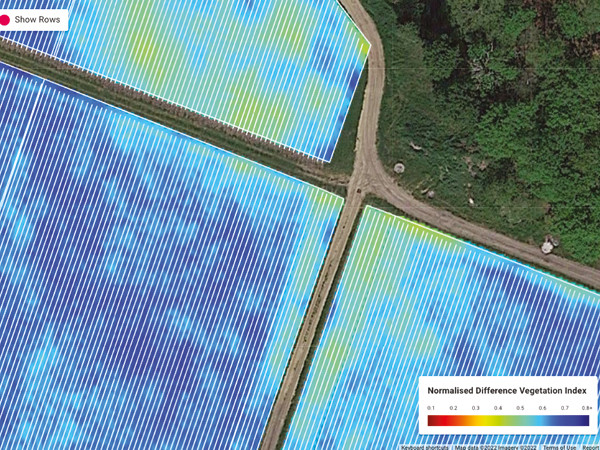

“We can ask, ‘What is the harvest date for this year?’,” says commercial director, Christopher Pang. “Or, ‘How are the vines maturing across the growing season?’. The really cutting-edge stuff is the vineyard health-monitoring tool, which shows the health and vigour of the vegetation to 0.5m per pixel imagery, (every pixel on the screen is equivalent to half a metre in the vineyard). Our maturity maps also show variation in sugar levels within the block.”

Such benefits have drawn the attention of a host of names. Bernard Magrez and Domaine Lafage are both clients, though the largest is perhaps Pernod Ricard.

In 2021, Deep Planet began working with the French giant’s winemakers in south-eastern Australia in order to predict the yield and maturity of their crops at scale. The project spanned 1,000ha, covering multiple wine grape varieties across several key regions.

“With Pernod Ricard, we've helped them save on harvest logistics,” co-founder and COO Sushma Shankar, tells Harpers.

“These are large producers which contract vineyards across the region, so they’re looking for efficiency: for example, calculating how many pickers or trucks are needed for harvest. They can send out 100 trucks and some of them come back with no grapes. This is a big country, with an enormous number of grapes, so being able to predict yields and harvest dates has real savings.”

↓

‘Saving water, boosting harvests’

The savings are clearly there for the environment, too. The project began back in 2018 as way of helping agriculture more broadly with water and soil moisture management. One of its primary mottos remains, ‘Saving water, boosting harvests’.

The first round of funding came via the European Space Agency, which helped to spur on its work with the wine industry. Wine remains the project’s primary focus.

The founding trio, which also includes Aussie-based CEO David Carter, is acutely aware of the impacts of water shortages and drought on agriculture.

According to Unicef, a third of the world’s population is living in areas that suffer from severe water shortages for at least one month each year. By 2025, Unicef predicts half the world’s population will face water scarcity – and, by 2030, 700 million people could be displaced.

“At the beginning of the project, some of the oldest winemakers in Oz reached out,” Shankar explains. “They said, ‘We have our own vineyard data, but we don’t know exactly what to do with it’. We knew there was a problem with water. But since then, we’ve been exploring its effects more and more.”

She continues: “Over the next 50 years, with the climatic conditions the planet is facing, 75% of the world’s existing vineyard area could potentially disappear. New vineyards could be planted, of course, but it’s still a major challenge. With water, some use cover crops or pruning to avoid irrigation. A lot of work is being done on how to manage inter-soil moisture. There isn’t just one way to apply water.”

As the wine industry continues to suffer from challenges associated with water management, climate variability and crop health, Shankar also predicts that 20% of the global vine crop is lost annually, to the tune of £90bn.

Part of Deep Planet’s strategy to counteract this is its work with winemakers such as Rathfinny. Based in Sussex, the estate has been liaising with Deep Planet on issues such as vine stress and how to manage it throughout the season. VineSignal’s high-resolution imagery can show which rows or blocks are under stress. Deep Planet also has further links with the UK: it recently won a grant with Innovate UK to look at vine productivity, with funding coming from the UK government.

“With my background in scaleable tech, [third co-founder] Natalia Efremova’s expertise in computer vision, and David’s knowledge of soil modelling, we realised we could address global scarcities and try and do something that’s good for the planet,” Shankar concludes.