CIVB: Talking Bordeaux

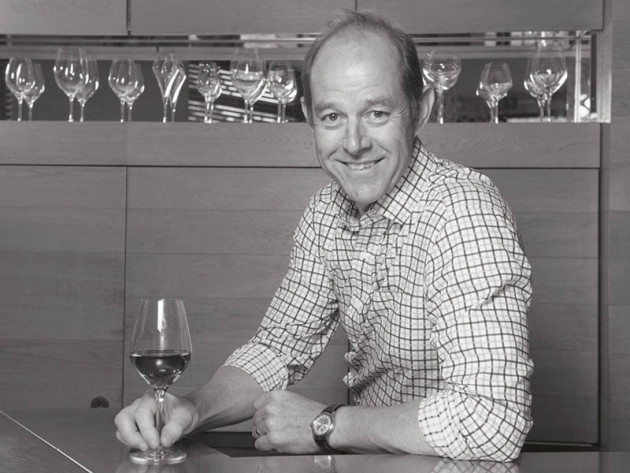

CIVB president Allan Sichel talks to Andrew Catchpole about the challenges and changes faced by this multi-faceted region.

Allan Sichel exudes the calm, statesman-like manner that you might expect from a figurehead of what many consider to be the pre-eminent wine region in the world. As president re-elect of Bordeaux’s generic body the CIVB (Conseil Interprofessionnel du Vin de Bordeaux), however, he clearly has a firm grasp on the issues facing the growers and merchants it represents, along with an open-minded view on the steps that Bordeaux must take to retain its long-established pole position. And, says Sichel, despite its flagship status, Bordeaux’s reputation and success is far from a given.

Keeping the name out there is an “ongoing challenge”, he suggests, with many people – especially younger generations – “intimidated by Bordeaux wines”. Then there’s the misconception that Bordeaux’s most famous and high-end names define the region, whereas they account for around 3% of production. Those wines are in demand, of course, but of the other 97%, Bordeaux has had to cope with several challenges.

One is the dramatic ongoing drop of per-capita wine consumption in its home market over the years, which the region still relies upon for some 55% of its sales. Then there’s the decimation of sales into China, to which at the peak Bordeaux was exporting 650,000hl a year – three times the volumes exported to the UK – until “economic changes brought that tumbling down” to around half that amount today.

Furthermore, of course, there’s the growing threat of the climate crisis, which is also having a significant impact, with extreme weather events to the fore, as witnessed in the frosts, hails and unseasonable downpours impacting recent vintages, along with an overall warming.

Relating all of this in the CIVB’s Bordeaux offices, Sichel goes on to explain what this means for the region and how its marketing activities are being targeted to evolve the perception of Bordeaux and its wine offer.

“There’s a lot of complexity in Bordeaux so it’s hard to sum up [the region] in one message,” says Sichel.

“We want to show interesting aspects of Bordeaux, and show change, and put different

topics to different segments of the market at different times. And that gives us a whole bank

of conversation topics that we can pull out.”

Pushed on any unifying message, Sichel lands on the human aspect and the need to connect producers with wine drinkers – which has been a very strong part of the recent campaigns by Bordeaux to put glasses in thousands of hands from Leon to Liverpool.

“We are developing more and more events where we are bringing growers into contact with

the end consumer,” he says.

However, he adds: “We are often perceived as one big, homogenous industry, but what we are also doing is showing that behind that are individuals, with different ideas, different philosophies, different experiences, so a lot of diversity in what they are doing and the wines they are making.”

The ‘97%’ step up here, and especially wines between €10 and €15, where Bordeaux has been working hard to relay the value and quality – able, insists Sichel, to take on rivals from anywhere in the world with regard to character and pricing.

Similarly, on the aforementioned diversity, Bordeaux and the CIVB have been busy pushing the region’s whites and rosés, along with a more recent campaign focusing on the crémants, quite literally adding more sparkle to the collective vinous offer.

Wine tourism is also playing an increasingly important role in selling Bordeaux, and something that Sichel is keen to push further. His offices sit above the CIVB’s Bordeaux Wine School and adjacent wine bar, which help draw some 450,000 visitors to the region a year.

↓

Embracing change

If the current marketing of Bordeaux is dynamic, then it’s also fair to say that the region’s growers are embracing change, not least in the much commented on addition of new varieties to the vineyards.

“We started the process over 10 years ago, with 250 possible candidates, in terms of new grape varieties,” says Sichel, “bringing that down to four reds and two whites, accepted by AOC Bordeaux.”

Arinarnoa, Castets, Marselan and Touriga Nacional, plus Alvarinho and Liliorila, are the varieties now being planted (or revived), which will initially be allowed to comprise no more than 5% of any given vineyard area and no more than 10% of a given blend. The longer-term view is that these will help combat the effects of climate warming, allowing both viticultural advantages and flexibility in Bordeaux’s typically blended wines.

Sichel says that climate change was originally “an accelerator” for Bordeaux in achieving bigger, more structured styles, but the region is now facing the double challenge of a world increasingly looking for fresher, lighter styles in a still warming environment.

This, currently, is not a problem with mainstays such as Cabernets Sauvignon and Franc, or

Petit Verdot, he adds, but Merlot is coming under pressure, with some growers already reducing

and grafting over the latter.

“At the moment, our harvesting window is still acceptable, but as temperatures increase Merlot will be the one that falls out. So there will be less planting of Merlot, but more Cabernets Franc and Sauvignon, and more Petit Verdot. And the introduction of these new grape varieties is looking further ahead.”

Changing viticultural and winemaking practices are also much in evidence, with less extraction, better canopy management and even north-facing slopes all playing a role.

“Climate change is about warming, but it’s also about extreme weather events – drought, excessive heat, hail, frost, too much water at the wrong time – so we have to ask ‘how do we improve the industry’s resilience to these very powerful phenomenon?’”, adds Sichel.

The implications for the industry have certainly sunk in, as 75% of vineyards now have some form of certified environmental approach, up from 35% in 2014, with the CIVB pushing for more, backed by an SMO (systèm de management) introduced to help the environmental and social transformation of Bordeaux.

Also driving all of this evolution is a change of mindset, as a younger generation takes up the reins.

“It’s a generational change, [growers and winemakers] coming through that have travelled, are open-minded, more confident and more collaborative, which means more creativity and less standardisation in terms of the possibilities offered with wine styles and varieties.”

It’s a new face of Bordeaux – a far cry from the old guard – that is more in tune with what the market wants, bringing a new-found freshness, approachability and creativity to the wines. And for wine drinkers worldwide, this all bodes well.